Open Cities 17 Mixed Communities – Openness or Myth?

Mixed communities could be construed as an indicator of an open city. This presumes a definition of mixed communities. The Future of London’s Social Housing was discussed at a seminar held at the London School of Economics on 19 February 2010. This offers an opportunity to explore the contribution of social housing to mixed communities and, by extension, to the openness of cities. Politicians and practitioners (local authorities and housing associations) discussed the financial and political context of fit-for-purpose social housing provision against the backdrop of the London Plan revision and the impact of the economic recession.

Housing Remains Segregated in London

London’s history is one of increased owner occupation, sharp decrease of private rented housing and relatively less fluctuating socially rented provision, although both the provider and the type of housing provided changed considerably over the last two generations. The question here is whether, and how social housing can contribute to make London a more open city.

Christine Whitehead shows that despite many changes, Social housing remains unevenly distributed in London with concentrations of to up to 80% in inner and east London, and very little social or even affordable housing in the outer suburbs, despite targets to even this out in the London Plan. Dwindling resources for social house building and maintenance will preclude any progress.

Considering that housing constitutes some 60% of London’s built environment and that service workplaces are highly concentrated in the City and the West End, mixed tenure should make a major contribution to mixed communities. Uneven quality, physical form and spatial distribution of social housing, its concentration reinforced by large scale urban renewal, its lack of affordability by those most in need shape existing communities. No matter how boundaries are drawn, London lacks mixed communities which, by inference, hampers the city’s openness.

Alternative Strategies and Personal Choice

Ann Powers explained that the point system of council housing which prioritises access of the most needy, the unemployed, disabled, low income families, single parent households, ethnic minorities, refugees, etc led to great concentrations of multiple deprivation and stigmatised large public housing estates. She maintains that current social engineering of trying to mix tenures through right to buy, intermediary arrangements, part purchase part rental, etc, is not creating genuine social mix. Instead she advocates less socially destructive, step by step housing refurbishment involving the tenants. This may be cheaper, but by reducing housing mobility this may not necessarily improve London’s openness.

Dia 3 examples of large scale housing estates and ‘soft’ refurbishment (Aylesbury estate). source: BBC

Segregation occurs even in areas where school catchment areas include both social housing estates and private owner occupied housing. Moreover, people vote with their feet and self-segregate by moving to better areas as soon as they can afford it. There they tend to oppose influx of social housing, thereby reinforcing the ‘nimby’ effect. Examples exist though of new sustainable communities designed with social cohabitation in mind.

Dia 4 BedZED an eco-village in London’s suburbs with mixed tenure and ‘live-work’ spaces. source Judith Ryser

A London Lab of Openness?

A large cosmopolitan city like London could act as a laboratory to find out why openness may be resisted, where and by whom, and how it could be brought about, with what legitimacy, and what durable effect?

Some answers may be embedded in the contributions two politicians from opposite parties made to the seminar. The Borough of Croydon in the outer southern suburbs is atypically dense and urban. Its conservative government is cooperating with various agencies to provide social housing, while making a concerted effort to use existing housing equitably. The labour-led Borough of Greenwich in the eastern suburbs has a pro-active housing policy for its mixed ethnic community, offering a wide range of tenure. It is engaging the local population in new design, and existing tenants in the improvement and management of their housing areas. Albeit with opposite political motivations, both Boroughs are aiming at a broader spectrum of housing supply.

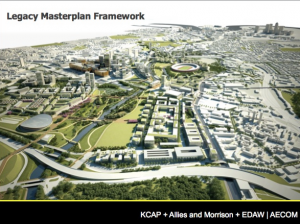

Whether and how much they can contribute to redress London’s spatial social segregation depends on the many other boroughs who do not share their approach. Must higher income areas resist social housing while the traditional working class areas have great concentrations of social housing and lack attraction for the middle classes. It remains to be seen whether the legacy of the Olympic Games 2012 will be able to redress this long standing historic segregation.